Starting point for simple ransomware detection

Catch spooky renames before they spread.s

Intro

You can check this project out on GitHub, and the minifilter can be found here!

Some time ago, I wrote a blog post as part of the Sanctum EDR strategy to detect Ransomware. I didn’t commit at the time as there were no bindings for writing Filter Drivers in Rust (and there still aren’t). But alas, it has been something I have been wanting to do now for a few months so I decided to brush the cobwebs off my C skills and get to work.

Architecturally how I would like ransomware detection to work is simple;

- A filter driver sends signals to the usermode engine which can process filesystem events, such as file name modifications or write access to a file.

- Checking for known ransomware file extensions that we will implement in this post.

- Track how many of these events are happening across the entire system.

- Keeping an eye out for 1 process making multiple write operations across lots of different directories.

- Correlation of what file type is being modified.

- Inspection of modified files to examine their entropy, being a heavy indicator of ransomware.

There are probably a few other cool things we could do; but this should be a good start.

In this post we will implement the filter driver (in C) which can intercept file system events to look for file change events; most notably changing the file name and write access to a file by a process.

The POC for this is incredibly simple, as all complex investigations should be at their inception. We will simply write some bytes to a file, and rename it, giving it the extension of a known LockBit ransomware variant.

You should check the source code fully if you wish to implement this yourself as I provide some additional safety checks there which I have not copied here, as to not be overly verbose in this blog post.

Filter drivers

On Windows, a filter driver is a driver that sits in a stack and observes, modifies, blocks, or changes filesystem events as it flows between user mode and the core driver that actually services the request. The big win is leverage: we get visibility and control at a chokepoint where lots of activity naturally converges.

These begin their life just like any other driver, with a DriverEntry function. In there, instead of setting up the driver

like we have done previously, we use the Flt function families to register ourselves as a filter driver, and tell the system

where our callback functions are.

For this, we need a few globals:

// Receives the handle to our filter driver

PFLT_FILTER g_mini_flt_handle = NULL;

// What callbacks do we want to hook

CONST FLT_OPERATION_REGISTRATION g_callbacks[] =

{

{

IRP_MJ_CREATE,

0,

PreOperationCreate,

PostOperationCreate

},

{

IRP_MJ_SET_INFORMATION,

0,

PreOperationSetInformation,

PostOperationSetInformation

},

{ IRP_MJ_OPERATION_END }

};

// Registration data such that the system knows where to find our callbacks & routines

const FLT_REGISTRATION g_filter_registration = {

sizeof(FLT_REGISTRATION),

FLT_REGISTRATION_VERSION,

0,

NULL,

g_callbacks,

InstanceFilterUnloadCallback,

InstanceSetupCallback,

InstanceQueryTeardownCallback,

NULL,

NULL,

NULL,

NULL,

NULL

};

I won’t go into detail around the set-up of filter drivers; I used this excellent article by Sergey to get myself set up.

Callbacks

For this; we have two callback ‘families’ we are interested in that you can see above in the g_callbacks array. The first is a CREATE event, the second is a SET_INFORMATION event. We set function pointers as to where our callbacks live for each event. In my case, I am not bothering with the Pre element, so these simply instruct the minifilter to continue the event until our Post handler is invoked. An example of what this looks like is as follows:

FLT_PREOP_CALLBACK_STATUS FLTAPI PreOperationCreate(

PFLT_CALLBACK_DATA data,

PCFLT_RELATED_OBJECTS flt_obj,

PVOID* completion_ctx

) {

UNREFERENCED_PARAMETER(completion_ctx);

UNREFERENCED_PARAMETER(flt_obj);

UNREFERENCED_PARAMETER(data);

// This tells the filter stack to continue; but for our post callback to be invoked

return FLT_PREOP_SUCCESS_WITH_CALLBACK;

}

So, now we have two events to handle. Let’s start with IRP_MJ_SET_INFORMATION.

IRP_MJ_SET_INFORMATION

This event is called when the system sends an IRP to set metadata about a file or file handle. The perfect example for this, is a file rename, such as in the case of what Ransomware would like to do for the iconic spooky file extensions.

The idea of the minifilter is mostly to be a telemetry logging service for us; but I see no reason why we cannot use this opportunity to stretch this blog post to detect something bad going on.

As outlined on trendmicro, a particular LockBit ransomware variant was using the file extension .HLJkNskOq after encrypting a file. This is a nice static IOC which would be fairly unusual for a benign process to be using.

So, first, lets define this in an array:

const LPCWSTR KNOWN_RANSOMWARE_FILE_EXTS[] = {

// Associated with Lockbit

L".HLJkNskOq",

};

And define our prototype for handling IRP_MJ_SET_INFORMATION.

FLT_POSTOP_CALLBACK_STATUS FLTAPI PostOperationSetInformation(

PFLT_CALLBACK_DATA data,

PCFLT_RELATED_OBJECTS flt_objects,

PVOID completion_ctx,

FLT_POST_OPERATION_FLAGS flags

) {

UNREFERENCED_PARAMETER(flt_objects);

UNREFERENCED_PARAMETER(completion_ctx);

UNREFERENCED_PARAMETER(flags);

// ..

}

The very first thing we want to do here, is to ensure we are only dealing with INFORMATION events where the file was renamed. We can check this as follows:

//

// Only filter for now on rename events in this handler

//

FILE_INFORMATION_CLASS info_class = data->Iopb->Parameters.SetFileInformation.FileInformationClass;

switch (info_class) {

case FileRenameInformation:

case FileRenameInformationEx:

break;

default:

// post_complete is just a label to deal with memory cleanup and returning

goto post_complete;

}

The next thing to do, is to get extended file name information for the event. I have noticed simply using the data argument, we only get 3 chars in the file extension, which is not useful for us. Thankfully, there is the FltGetFileNameInformation API which allows us to get normalised information about a file from the minifilter event.

To use this API, we need to set a stack variable to receive a pointer to the allocated information, and to then call the API, and the subsequent FltParseFileNameInformation:

PFLT_FILE_NAME_INFORMATION name_info = NULL;

NTSTATUS status = FltGetFileNameInformation(

data,

FLT_FILE_NAME_NORMALIZED | FLT_FILE_NAME_QUERY_DEFAULT,

&name_info

);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status)) {

DbgPrint("[-] Failed to get file name information in filter driver.\n");

goto post_complete;

}

// Now parse the information so we get the full name, not just the last 3 file ext chars

FltParseFileNameInformation(name_info);

It is also important to make sure we free the PFLT_FILE_NAME_INFORMATION before we return from the function:

if (name_info != NULL) {

FltReleaseFileNameInformation(name_info);

}

Note, the rename information is also available in data->Iopb->Parameters.SetFileInformation.InfoBuffer, which I need to investigate

further to see if both sources always contain the same thing, or if there are differences between them. This should also be available

in the PreOp callback I believe, which may be a better place for this check (in production).

We can then grab the full file name, and compare it to the array of (likely) known bad IOCs in terms of file extensions:

BOOLEAN IsFileExtKnownRansomware(PUNICODE_STRING input) {

if (input == NULL) return FALSE;

if (input->Length == 0 || input->Buffer == NULL) return FALSE;

size_t input_num_chars = input->Length / sizeof(WCHAR);

for (size_t i = 0; i < RTL_NUMBER_OF(KNOWN_RANSOMWARE_FILE_EXTS); ++i) {

//

// Safety checks

//

if (KNOWN_RANSOMWARE_FILE_EXTS[i] == NULL) continue;

size_t num_chars_ransom_ext = wcslen(KNOWN_RANSOMWARE_FILE_EXTS[i]);

if (input_num_chars < num_chars_ransom_ext) continue;

//

// Now loop through the chars at the end of the input string, and try match

// for the known ransomware extensions

//

BOOLEAN total_match = TRUE;

size_t start = input_num_chars - num_chars_ransom_ext;

for (size_t j = 0; j < num_chars_ransom_ext; ++j) {

size_t idx = start + (size_t)j;

if (input->Buffer[idx] != KNOWN_RANSOMWARE_FILE_EXTS[i][j]) {

total_match = FALSE;

break;

}

}

if (!total_match) continue;

return total_match;

}

return FALSE;

}

If we get a match, we can alert a relatively high fidelity signal to the collector / usermode engine which can then inspect the file, look at its entropy, etc.

We could take this a step further in the driver, and perhaps freeze the calling process’s threads until the usermode element has had chance to inspect the file and any other signatures it has, to try limit the impact of the impending ransomware sample.

We can also at this point retrieve details about the process making the modification without too much overhead, and print / send back to userland:

// To get the image name of the executing thread

NTSTATUS LookupImageFromThread(PETHREAD p_ethread, PUNICODE_STRING* image) {

if (image == NULL) {

return STATUS_INVALID_PARAMETER_2;

}

*image = NULL;

PEPROCESS p_eprocess = IoThreadToProcess(p_ethread);

if (p_eprocess == NULL) {

DbgPrint("[-] Failed to get EPROCESS.\n");

return STATUS_UNSUCCESSFUL;

}

NTSTATUS status = SeLocateProcessImageName(p_eprocess, image);

if ((!NT_SUCCESS(status)) || *image == NULL) {

DbgPrint("[-] Failed to locate process image.\n");

return STATUS_UNSUCCESSFUL;

}

return STATUS_SUCCESS;

}

// This goes in the filter callback itself, to retrieve the PID of the process:

int process_pid = HandleToLong(PsGetProcessId(IoThreadToProcess(data->Thread)));

We also need to be sure to free the PUNICODE_STRING when we are done with it:

if (image != NULL) {

ExFreePool(image);

}

IRP_MJ_CREATE

This IRP is sent on request to open a handle to a file object or device object. In our minifilter we can use this to inspect when a process is trying to open a file.

For now, we can keep most of this callback simple, and only filter on events which are write handles to a file. To do this we can use the below as a filter inside of the callback:

ACCESS_MASK access_mask = data->Iopb->Parameters.Create.SecurityContext->DesiredAccess;

if (access_mask & (FILE_WRITE_DATA | FILE_APPEND_DATA | FILE_WRITE_ATTRIBUTES | FILE_WRITE_EA | DELETE)) {

// ..

}

We can use that to send the signal up to the collector, so it knows a process is trying to gain mutable access to files. As above, we can also gather information about the process image and the PID of the process which completed some mutable file event.

The ransomware

As I said in the intro, we want to keep a POC simple to align with the objectives of our starting point for a ransomware detection module. The below Rust code simply writes some junk to a file, and renames it to have the extension of the LockBit variant we are using as an example.

use std::io::Write;

pub fn change_file_name() {

const STARTING_FILE_NAME: &str = "test.txt";

let mut f = std::fs::File::options()

.create(true)

.write(true)

.truncate(true)

.open(STARTING_FILE_NAME)

.expect("could not open file");

// simulating writing encrypted data back to the file

let fake_data = "dsfujkhygkdsjuyfgvbsdkujyfgsdkujyfgfdsigujhkdsuifyhgds";

f.write_all(fake_data.as_bytes())

.expect("could not write bytes");

std::fs::rename("test.txt", "test.HLJkNskOq").expect("could not rename file");

}

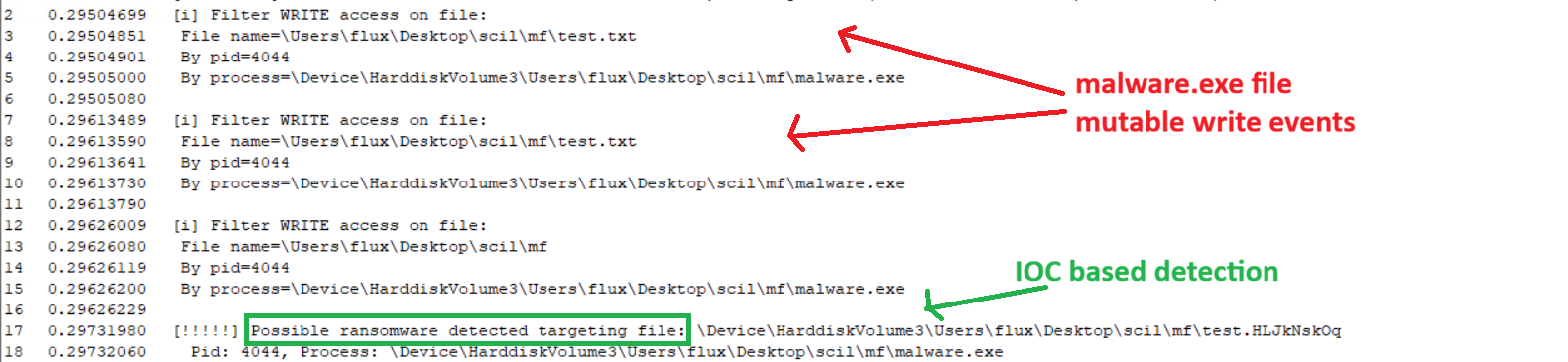

And this gives us the following result once our driver is up and running:

Next steps

For now, this is all! The next steps are probably to write the telemetry collection harness, which I am not doing this weekend. From there, the usermode collector could try process events, partially read parts of files which have been modified, and look for indications of ransomware.

It would also be an interesting idea to log in usermode how many processes are making n number of file change events every second, spread across the filesystem - it would be a strong indicator if a process was making a significant number of file change events, against files of high entropy, in a very short space of time.

I hope you enjoyed this, until next time!